Severe storms damage 300,000 acres of Wisconsin forests, leaving behind major wreckage

Landowners, foresters and loggers begin cleanup process for millions of damaged trees from July 19-20 storms

A series of storms that struck central and northern Wisconsin in late July severely damaged more than 300,000 acres of forest, leaving behind millions of flattened, broken and twisted trees, according to initial estimates by the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

Salvage operations began shortly after the July 19 and 20 storms, as timberland owners, loggers, mills and government officials scramble to figure out how the abundance of wood flooding the market will affect prices.

Heather Berklund, the deputy division administrator of forestry operations for DNR, said aerial surveys after the storms showed that 23,000 acres of country forests; 14,500 acres her agency manages, including state forests and parks; 530 acres of tribal lands; 53,600 acres managed under a tax law program; 51,400 acres in the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest and another 133,200 acres of privately held timber were damaged.

Storms were especially devastating to some private landowners, according to Nancy Bozek, executive director of the Wisconsin Woodland Owners Association, which had a number of effected members. Bozek said the storms covered miles of forest, resulting in 52 emergency declarations for affected towns, counties and villages.

“The damage is mind-boggling and I’ve never seen anything of this scale,” she said of the storms, which included at least 16 tornadoes. “It could easily total millions of trees and my heart goes out to those who have been affected. As many of them have told me, ‘I have insurance on home or cabin and things can be replaced, but you can’t replace a forest.’ It will take a lifetime for that to happen.”

Berklund said three main areas of the state were affected by the storms: Polk and Barron counties, Wood and Portage counties with a small amount into Waupaca; and Langlade and Oconto counties and a small amount into Marinette County. A fourth, isolated section of Sawyer County containing timber owned by the Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe, was also hit.

Forest Data Network’s latest pricing information will also show updated market impacts when the reports are published (click to subscribe to a report here). The DNR is also doing a market analysis to see how much salvaged wood will lower prices for landowners and public agencies.

“We are reaching out to mills, seeing what their capacity is and asking if they can expand in heavily hit areas,” Berklund said. “We’re also assessing market availability in other Great Lakes states to see if they can take additional wood.”

“Then there’s also the question of logger capacity to see if they have the flexibility to move on salvage sales as soon as they can.”

But she warned not all the wood will make it to mills.

“With a damage of this magnitude across the state, it is unrealistic that all the wood will be able to be processed and cleaned-up,” she said. "Agencies and landowners all have to prioritize the areas of greatest value based on land manager’s objectives and risk."

DNR: Insect and storm-damaged trees alert

See the full story from the Wisconsin DNR

Some insects and diseases can take advantage of storm-damaged trees and cause long-term damage to forest stands. Continue reading to learn more about these issues, how to deal with them and how to contact professionals who can help landowners make decisions about their land.

Pines are first priority

Storm-damaged pine stands should be a landowner’s top priority when deciding where to start. Salvaging pine is much more urgent than oak or other hardwood stands because damaged pines will quickly begin to stain, and insects and disease will rapidly infest the damaged trees.

Bark beetles quickly attack leaning, broken or uprooted pines.

Native bark beetles such as red turpentine (Dendroctonus valens) and pine engraver (Ips pini) will rapidly attack damaged trees that are leaning, broken or uprooted as well as fresh logs in log decks. Bark beetles will continue to attack storm-damaged trees and can move on to attack healthy pine once their populations grow. For more info on bark beetles, check out the WI DNR bark beetle factsheet.

White-spotted sawyer (Monochamus scutellatus) is another native beetle that will move in when a pine tree is nearly dead (or freshly cut). If you’ve ever stood by a conifer log pile and heard scratchy chewing noises, you were listening to this native pine sawyer.

Armillaria is a fungus that attacks the roots of storm-damaged trees. Tree mortality from armillaria root disease won’t show up until 1-3 years after the storm.

The bottom line to minimize insect and disease issues is to harvest your pines as soon as possible after the storm. Check out this printer-friendly factsheet for more information about salvage harvests, pests and replanting in storm-damaged pine stands.

Heterobasidion root disease in pine and spruce

Heterobasidion root disease (HRD), previously known as annosum, is a serious fungal disease of conifers, particularly pine and spruce. Infected trees decline and eventually die. Infection occurs when a spore lands on a freshly cut stump and germinates. Once in a stand, the disease can move from an infected stump to nearby trees through root contact, eventually killing those neighboring trees.

If a pine or spruce stand is within 25 miles of a known HRD pocket and a harvest or salvage will be done, it is recommended to treat pine and spruce stumps with a preventative fungicide within 24 hours of the tree being cut. To find out if you’re within 25 miles of a known HRD pocket, check out the interactive HRD web map.

When salvaging storm-damaged trees, it may be difficult to quickly find a logger who is certified to apply pesticides or one who has the equipment to spray the stumps as they are being cut. It may also be impractical or impossible for logging equipment to cut and treat those trees that are down or broken. Although efforts should be made to arrange preventive stump treatment, under this type of emergency harvesting, treatment of stumps at the time of harvest may not be practical. Refer to the HRD guidelines and the modifications that reference salvage (Chapter 3, Modification 4, and Chapter 4, Modification 4). For more information about HRD, visit the DNR HRD webpage.

Hemlock borer

Hemlock borer (Melanophila fulvoguttata) is a flatheaded wood-boring beetle whose immature stage bores into stressed or recently killed hemlocks. Storm-damaged hemlocks provide a good breeding ground for hemlock borers, and their populations grow large enough that they attack living hemlocks. To avoid hemlock borer attack on living hemlocks, promptly salvage windblown hemlock following a storm event. If you must thin standing trees around living hemlocks, the intensity of thinning should be as light as possible.

Oaks and other hardwood stands

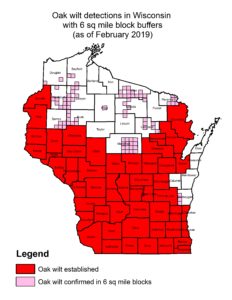

Counties shown in red have oak wilt throughout the county, although it may not be in every stand. Oak wilt is not common in northern Wisconsin.

Don’t rush – deterioration of oak is not an immediate concern. A thoughtful approach to salvaging your oak stands will be more beneficial in the long term. Oaks with broken roots or major branch/stem breakage may be attacked by the native two-lined chestnut borer (Agrilus bilineatus). Larvae of this beetle bore under the bark of oaks and can girdle and kill branches or entire trees. Branch mortality or whole tree mortality due to this insect will show up 1-3 years after a major stress event like these storms.

The good news is that the July 19 and 20 storms occurred after the high-risk period for new oak wilt infections. Oaks are highly susceptible to infection by the oak wilt fungus (Bretziella fagacearum) during spring and early summer (April 15 – July 15 in the north and April 1 – July 15 in southern Wisconsin). Oaks in the red oak group will be killed completely while just a branch may die on white and bur oaks.

If salvage of stands with oak will occur next spring during the high risk period, please see the oak wilt guidelines for information on harvesting to minimize introduction of oak wilt There is a guideline modification for salvage harvesting that you could consider, so check out the guidelines to decide what is best for your property. Read more about oak wilt on the DNR oak wilt webpage.

What to salvage

Uprooted trees, and those with completely broken tops, will die and should be salvaged. Standing trees with some broken branches are judgment calls. A general rule is to salvage the tree if more than 50% of the crown or top is broken, but there may be situations when these damaged trees could be left to help your forest recover. A professional forester can help you with these determinations. Trees that are leaning may have broken roots or broken stem fibers and should be considered for salvage. Check locally for wood disposal sites or refer to the DNR page on cleaning up storm debris.

Firewood

Storm-damaged trees can be utilized for firewood, but you should be careful not to move firewood long distances and risk introducing invasive species like emerald ash borer, gypsy moth and oak wilt to new areas. Instead, let the firewood age in place and burn it locally. For more information, visit the DNR firewood page. Always use proper protective equipment when operating a chainsaw.

Continued monitoring

Trees do not recover from stresses very quickly. Dieback, and even mortality associated with the storm, could continue for 2-3 years. Hail damage associated with the storms may not be apparent until next spring. You should continue to monitor your storm-damage stands for several years, especially if additional stresses occur in the year or years after the storm damage (such as a drought, defoliation, etc.). If you notice trees dying in the year following the storm or even two years after the storm, you should discuss this with your forester.

Replanting – when do you start over?

If you have a pine stand that was salvaged and you plan to replant to pine on that site, wait! Pales weevil (Hylobius pales) is a native insect that will infest freshly cut pine stumps. That alone is not a concern, but as new adults emerge from stumps, they must do a “maturation feeding” on conifer twigs, which can girdle them. If the only “twigs” available are the seedlings that you just planted then they will feed on those, possibly killing the seedling and causing extensive failure of your new planting. Wait for the second springtime following your salvage/harvest before you replant. Example: you salvaged your stand in August 2019, you should not replant until the spring of 2021. Another example: you salvage your stand in May 2020, you should not replant conifers on that site until spring of 2022.

Talk with a professional

If you’re still unsure of how to proceed with making decisions about the storm damage on your land, you should contact a professional forester or forest health specialist for insect and disease questions. You can also find lots of resources and information on recovery from the storm at the Wisconsin DNR storm damage page. Major storms like this can devastate a landscape and deal a crushing blow to the family forest. Discussing your options with a forester and creating a game plan that will benefit you and your land will start you on the road to forest recovery.

Berklund said the DNR wants to let landowners know that while downed trees can lay on the ground for one year and not suffer much deterioration, they should try to salvage it as soon as possible to avoid disease and other problems. In addition, she noted, it can present a fire-danger hazard.

She also said the state has timber landowner grants available to reduce costs of reforestation. More information on this program on the DNR’s website, she added.

Bozek said mills will be flooded in coming months with many species of wood as people clean up the storm damage. Like Berklund, she said she worries some may be unable to take the heavy flow.

“Still, we are encouraging people to be proactive and clean up quickly. We believe if the trees are left on the ground, it can attract infestations of insects and disease and become a fire hazard over time. It also makes replanting easier if the downed timber is cleaned up.”

Bozek also warned hard-hit timber owners to be wary of “storm chasers” who take customers’ money and move on after performing little work.

“People should work with reputable local foresters and loggers, many of whom live in your communities, if at all possible,” she said. “There will be some who will come from outside, but still be from Wisconsin or the UP (Michigan’s Upper Peninsula) because of the huge volume.”

“Regardless, they need to be cautious, get references and always use a written timber-sale contract. It’s important to clean up storm damage, but unless you have safety issues, it isn’t an emergency. So you should follow the proper measures of any timer harvest, protecting yourself with a written contract specify who is responsible for what.

She said her members and other timber owners can go to wisconsinwoodllands.org and search for storm damage to find a series a links to help them cope with the effects of the storm, including sample contracts.

Buzz Vahradian, a forester and landowner, has timberland in Portage County that was flattened on the 20th, and property near Hollister that was hit on the 19th.

“We had damage to our buildings, but they can be repaired,” mused Vahradian, who said he will be extremely busy with salvage work as a forester. “You can’t do that with the trees and on a personal level, that’s hardest to take.”

He said he had 20 acres of fine-quality northern red oak that he and his wife, Marsha - also a forester - bought 28 years ago. He said they thinned it in 1995 and again in 2013, removing the poorest quality timber and retaining the top-performing trees - mostly for veneer.

“They continued to grow and now all of our work is for naught,” he said. “The best stuff is damaged by storm. We’ll be able to salvage, but the quality of what we had was really high quality, probably worth $600 a thousand board feet on the stump. Now, we’ll get perhaps $150. Mother Nature sure threw a monkey wrench into our plans.”

Brian E. Clark is a contributor to Forest Business Network. He formerly was a business writer for the San Diego Union-Tribune and also wrote for newspapers in Washington State. He's also a regular contributor to the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel and the Los Angeles Times.